Previously: Burning oil is brilliant

Category Archives: Economics

Objection: China is worse

People look at the oil sands and say: “Yes, Canada is profiting off the destruction of the whole world, but we are a small part of the problem. China is doing so much worse, building new coal-fired power plants every week. Why should we deprive ourselves, when others will produce ruin for us all anyhow?”

There are many problems with this analysis. For one thing, China is pursuing its current model of development because it seems to have worked for countries like Canada, the United States, and Japan. If the richest and most technologically able countries get serious about a zero-carbon energy system, and they show that it can be done, countries that are developing rapidly now will have a new model to at least consider. Given the many disadvantages of fossil fuels, from air pollution to dependence on exports from volatile regions, a development strategy that is both credible and focused on renewables could have a lot of appeal in places like China, India, and Brazil.

Secondly, there is a suicide pact mentality that accompanies the decision to keep emitting greenhouse gas pollution recklessly because others are doing so. It is true that if just Canada abstains, and suffers lost resource revenues because of it, climate change will probably proceed to about the same extent as it would if Canada just kept cashing in on oil and gas. But the behaviour of other states is not independent of our behaviour, and other people care about the reasons for our actions. If Canada said: “We are going to leave fossil fuels underground, for the good of all humanity. We urge you to do the same.” it would at least advance the international discussion and focus attention on the key question of what proportion of all the world’s fossil fuels we choose to burn.

Thirdly, Canada’s impact is not trivial. When politicians boast about how the oil sands are a reserve as large as those of Saudi Arabia it should make us worried. Burning massive reserves of fossil fuel produces massive amounts of greenhouse gas pollution, even if you do manage to avoid causing too much local air and water pollution in the process of digging those fuels up. Canada’s giant fossil fuel reserves are a threat to the whole world, insofar as they are capable of making climate change that much more dangerous.

Canada cannot avert disaster on its own. Nobody can. But universal disaster is nonetheless an outcome we must avoid, and achieving that requires overcoming a status quo system that remains determined to burn all the world’s coal, oil, and gas and only then start thinking seriously about what energy sources will replace them. We need to do better than that, and one way to contribute to that effort is to refuse to use the bad behaviour of others as an excuse to continue to behave badly ourselves.

Climate change and conflicts between generations

“The second reason behind Kyoto’s failure is its intergenerational aspect. Most analyses describe the climate-change problem in intra-generational, game-theoretic terms, as a prisoner’s dilemma or battle-of-the-sexes problem. But I have argued that the more important dimension of climate change may be its intergenerational aspect. Roughly speaking, the point is that climate change is caused primarily by fossil-fuel use. Burning fossil fuel has two main consequences: on the one hand, it produces substantial benefits through the production of energy; on the other hand, it exposes humanity to the risk of large, and perhaps catastrophic, costs from climate change. But these costs and benefits accrue to different groups: the benefits arise primarily in the short to medium term and so are received by the present generation, but the costs fall largely in the long term, on future generations. This suggests a worrying scenario. For one thing, as long as high energy use is (or is perceived to be) strongly connected to self-interest, the present generation will have strong egoistic reasons to ignore the worst aspects of climate change. For another, this problem is iterated: it arises anew for each subsequent generation as it gains the power to decide whether or not to act. This suggests that the global-warming problem has a seriously tragic structure. I have argued that it is this background fact that most readily explains the Kyoto debacle.”

Gardiner, Stephen M. “Ethics and Global Climate Change.” (p. 21 paperback) in Gardiner, Stephen M. et al. eds. Climate Ethics: Essential Readings. Oxford University Press. 2010.

Problems with Keystone XL

Jim Robins has written an interesting article about climate change and opposition to the Keystone XL pipeline, which would carry bitumen from Alberta’s oil sands to refineries in the United States.

Carbon labelling

I don’t personally see much promise in the idea of putting labels on products that tell consumers how much carbon was emitted to produce them. Firstly, people don’t have much context for understanding what that means. Secondly, people don’t particularly seem to care. Thirdly, voluntary consumer action isn’t a sufficiently fundamental change to deal with the problem.

All that said, such labels could have benefits in unexpected places:

The process of calculating the carbon footprint for Walkers crisps revealed an unexpected opportunity to save energy. It turned out that because Walkers was buying its potatoes by gross weight, farmers were keeping their potatoes in humidified sheds to increase the water content. Walkers then had to fry the sliced potatoes for longer to drive out the extra moisture. By switching to buying potatoes by dry weight, Walkers could reduce frying time by 10% and farmers could avoid the cost of humidification. Both measures saved money and energy and reduced the carbon footprint of the final product.

The value of carbon footprinting and labelling lies in identifying these sorts of savings, rather than informing consumers or making companies look green. According to a report issued in 2009 by the Tyndall Centre for Climate Change Research at the University of Manchester, in England, “the main benefits of carbon labelling are likely to be incurred not via communication of emissions values to consumers, but upstream via manufacturers looking for additional ways to reduce emissions.†It is not so much the label itself that matters, in other words, but the process that must be gone through to create it.

While we are waiting for economy-wide measures like carbon pricing to be implemented, more limited initiatives like this are probably especially valuable.

Al Gore on Obama’s climate policy

As reported in The New York Times, former US Vice President Al Gore has written a long essay for Rolling Stone criticizing the climate policies of President Barack Obama.

Gore argues that Obama understands the scale of the problem and has appointed some good people to work on it, but that he has failed to effectively press the case for action.

Gore is clear about the uncertainty of whether America’s political system can deal with this key challenge: “It is about whether or not we are still capable — given the ill health of our democracy and the current dominance of wealth over reason — of perceiving important and complex realities clearly enough to promote and protect the sustainable well-being of the many. What hangs in the balance is the future of civilization as we know it”.

Here’s hoping Gore’s comments help to drive more serious attention to the problem of getting America to take world-leading action in response to this enormous threat.

Dealing with daredevils

The situation of those who are pushing for stronger action to combat climate change today seems a bit akin to the situation of paramedics watching a daredevil prepare for an insane stunt.

In the case of the daredevil, the stunt might be trying to jump across a canyon on a rocket-propelled motorcycle. In the case of the world today, it consists of burning a large portion of the world’s remaining fossil fuels, increasing the risk of catastrophic or runaway climate change.

The ideal option

In both cases, it is good advice to call off the whole thing. The daredevil risks plunging to his death (and I use the male pronoun advisedly here), being blown up by rockets, and so on. The world risks melting the icecaps, turning the sea to acid, severely disrupting global agriculture, dramatically increasing sea levels, and so on.

In both cases, the people with the power to choose the future course of action are unconcerned about the risks and keen to plow ahead forward despite them.

Fallback options

So where are we left, as paramedics/concerned citizens? Our fallback option is to do what we can to reduce the seriousness of the risks associated with the reckless course of action that has been chosen.

Paramedics can make sure they are prepared to deal with horrible burns and broken bones. They can carefully check the rockets on the motorcycle, and make sure they have plenty of the right sort of blood available for transfusions.

Those concerned about climate change can perform similar operations. We can try to improve the world’s resilience, when it comes to any radical changes that may occur in the future. This includes everything from trying to improve international cooperation to stockpiling potentially useful seeds to researching geoengineering techniques.

One big difference between the daredevil biker situation and the daredevil climate-alterer situation is that the man on the rocket bike is only really putting himself in peril. By contrast, all our our fates are connected to the choices of those now heedlessly digging up and burning fossil fuels. Rather than being like a crazed solitary motorcyclist, they are like the crazed driver of a bus which we are all riding. It would be nice to be able to convince them to behave in a less insane way. Failing that, we should be doing all we can to prepare for the likely consequences of their insanity.

Record energy use in 2010

This is not encouraging:

Robust growth was seen in all regions and in almost all types of energy use: the world consumed more of every main fuel bar one than it had in any previous year. Consumption of oil, which accounts for 34% of the world’s primary energy by BP’s calculations, rose by 3.1%. Coal, at 30% the number two fuel, was up by 7.6%, growing faster than at any time since 2003. Consumption of gas, which contributes 24%, was up by 7.4%, the biggest annual growth since 1984.

The growth in fossil fuels was so strong that although non-fossil-fuel energy also had a record year, its share of the world total primary energy decreased a little.

The universe doesn’t owe humanity its current standard of living. If we are going to retain something like it, we are going to have to find ways to power all of our essential needs sustainably.

Conference Board mitigation report

The Conference Board of Canada has produced a detailed report on the state of climate change policy in Canada:

Greenhouse Gas Mitigation in Canada (May 2011)

Their conclusions:

- More needs to be done to stop Canada’s GHG emissions from increasing and ensure a future where emissions targets are being met. We do not appear to be fully on that path just yet.

- Regionally focused provincial action plans could benefit from improved coordination between jurisdictions. This could help effectiveness and efficiency.

- Examining and tackling climate action items as a whole, rather than just individually, would provide greater confidence that the targets can be met. Effectively communicating the results of that analysis would help Canadians understand the priorities.

They also summarize their findings by saying:

- Lack of coordination between governments in Canada has hindered both the effectiveness of efforts to reduce GHG emissions and their efficiency (the cost per unit of reductions).

- Although provincial climate change action plans generally align well with the need to reduce emissions in particular sectors, it is difficult to measure the progress achieved.

- The national target of a 17 per cent reduction in emissions by 2020 and the individual prov- incial targets are being addressed through a complex, diverse, and opaque mix of instru- ments and programs.

- Carbon pricing is one area where a coordinated approach may produce more efficient results.

The report contains a lot of interesting and useful information on where Canada’s greenhouse gas pollution is coming from and what efforts have been made so far to try to reduce it.

Masters of nature

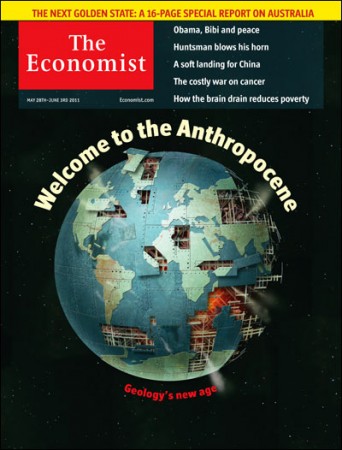

Interesting article in The Economist:

They do understand the science of climate change, but they don’t seem to have accepted the scale of effort required to keep it from becoming dangerous.