Don’t tell him, but I think Ezra Levant’s whole ‘ethical oil’ concept might be a psychological own goal for the people trying to promote the unrestricted growth of Canada’s oil sands.

The intent of the campaign is to draw attention to ethical abuses connected to oil from sources outside Canada. For instance, the lack of rights for women in Saudi Arabia. For people who are already convinced that Canadian oil is A-OK, the contrast between the appeal of buying oil from ‘good’ Canadian companies rather than ‘bad’ foreign companies or governments seems stark.

The reason why I think the slogan may be self-defeating is that by trying to draw attention away from arguments that Canadian oil is itself unethical, it reinforces the point that the choices we make about energy are ethical choices, not mere consumer choices. If you have come to accept buying fossil fuel as a perfectly ordinary part of life, with no more thought accorded to it than to buying a pack of gum or a bus token, seeing a blaring campaign about how Canada’s oil is ethical while oil from elsewhere is not may bring to mind the very arguments that the campaign is seeking to discredit.

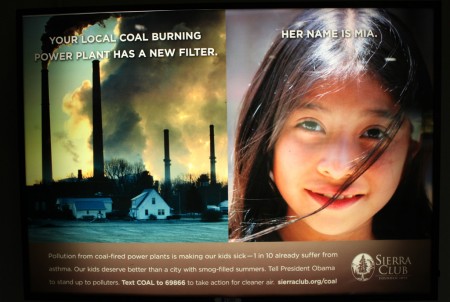

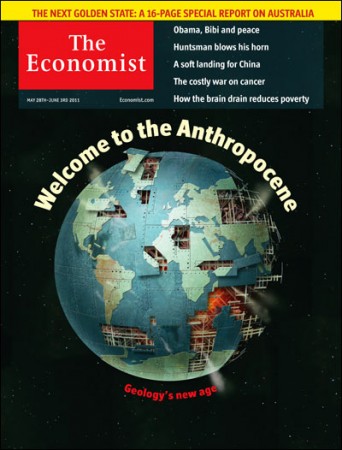

Plenty of people are aware of how problematic our society’s dependence on oil is. They are also aware of the dubious business dealings and environmental damage associated with all oil companies, including those in Canada’s oil sands. Oil companies are bad neighbours. When operating normally, they produce air and water pollution that saturates the world with toxic and cancer-causing chemicals. When something goes wrong, they cause catastrophic accidents that end human lives and spoil large areas of nature. Their operations and product are also inescapably linked with climate change. They profit while the people downstream and downwind suffer.

Reminding people that oil is an ethical issue may end up encouraging those with a balanced view to make less use of it and search more energetically for alternatives. To put it briefly, the oil industry loses when oil gets discussed as an ethical matter; for them, it is much better when people see oil amorally as an essential enabler for things they value doing like driving cars and flying in airplanes.

One side note about ‘ethical oil’ – one of their standard photo ops is to get a couple of women to wear black body-covering garments in the style of a burqa in front of environmental protests. The people being photographed often have a sign suggesting that OPEC is pleased by environmental protests, since they restrict hydrocarbon development in North America and keep the continent dependent on imports. On one level, these protests seem like fair comment on the oppressive government policies in some major oil-producing states. At the same time, it seems possible that the intention behind the protest is to take advantage of xenophobic or anti-Muslim sentiment. Appealing to the moral sentiment that women should not be subjugated by their governments is one thing, but using Islamophobia to try to discredit your opponents is much less morally upright.