Conservatives should love carbon pricing, and yet: Tories take cap-and-trade system off the table’: Kent.

Category Archives: Economics

Re-training

I have written before about how firms can no longer claim ignorance about the harmful effects of climate change. By now, they must know their greenhouse gas pollution causes harm to people.

That being said, it seems both ethical and politically pragmatic for governments to offer assistance to those people who are moving from industries that have little or no future in a low-carbon economy (such as the oil and gas sector) to those that have better prospects. Specifically, it seems appropriate to provide special programs and funds for retraining, since it is especially challenging for someone who has worked in one industry for a long span of time to move into another line of work unassisted.

Just as we should avoid circumstances where physical capital goes to waste (for instance, situations where tightening emissions regulations forced facilities to close before the end of their natural lives), we should be wary of discarding the knowledge and experience of workers in carbon intensive industries. With some assistance, effort, and ingenuity – however – it seems plausible that many of their skills can be applied usefully within an economy that is moving into line with what the climate can withstand.

Regulating climate pollution is constitutional and necessary

Aldyen Donnelly has written a problematic article on climate change policy for the Financial Post.

She is right to say that climate policies could create regional tensions in Canada. The big problem is that she ignores the victims of climate change. We need to stop burning fossil fuels because the alternative will hurt a lot of people. We need to take action despite the political barriers in the way.

The government can and must regulate greenhouse gas pollution. Otherwise, people will continue to profit from behaviors that impose suffering on defenceless members of future generations.

[Correction: 5:17pm] As originally written, this article wrongly referred to Aldyen Donnelly as male.

Climate change mitigation versus adaptation

There are two big sets of actions people can take as rational responses to the threat of climate change: mitigation and adaptation.

When we mitigate, we work to produce less greenhouse gas pollution. This limits how much warming can take place.

When we invest in adaptation, we invest in ways to protect ourselves from warming, like building sea walls to protect against rising sea levels.

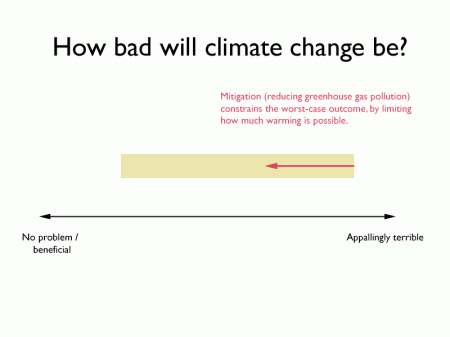

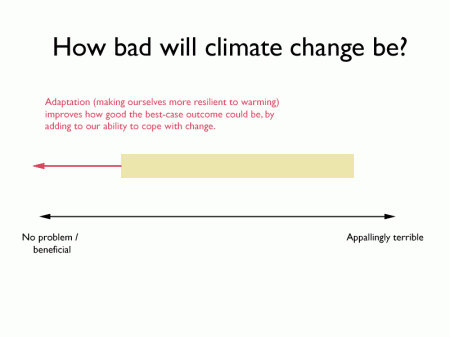

These two types of action have different effects on the risk humanity is facing. Specifically, mitigating reduces how bad the worst-case scenario will be. Adaptation improves how good the best-case scenario could be.

In the following graphics, the quantity being measured along the horizontal axis is human suffering. We cannot be sure exactly what the correct value is, but we have good reason to believe that it is within the range defined by the yellow bar.

With no action:

With mitigation:

With adaptation:

Given how bad climate change could be, I think the strong emphasis must be on mitigation. It is as though you are a patient, about to have an operation. The surgeon tells you that with the normal operation, there is a 10% chance that you will lose a leg and a 5% chance you could die. She then tells you that they can modify the operation in one of two ways:

a) Cut the chance of losing a leg to 5%

b) Cut the chance of dying to 2.5%

It seems far more sensible to choose option b.

With climate change, we don’t need to choose ‘100% mitigation’ or ‘100% adaptation’. Nonetheless, I think the same logic that lies behind the surgical decision lies behind the moral imperative for humanity to concentrate on mitigation.

Just think about the ice sheets

The question of exactly how bad any particular degree of climate change would be is extremely challenging to answer in advance. How much net human suffering would result from warming the planet 1°C? What about 2°C? 5°C? 10°C?

The answer to this question is important, since it helps to determine what the best course of action for humanity is. In theory, we could ban the use of fossil fuels tomorrow, shut down the world’s coal-fired power stations, park cars, ground airplanes, and start re-building the energy basis of society without the use of planet-warming sources of energy. Alternatively, we could ignore the problem for years, decades, or even centuries – allowing the planet to get ever-hotter until we completely run out of fossil fuels.

Here’s one way to simplify the problem: just think about the Greenland and West Antarctic ice sheets. These massive slabs of frozen water could raise global sea levels by 14 metres if they melted completely. That would have a gigantic human impact. Major cities like New York, Vancouver, Tokyo, and London would be seriously inundated. Whole countries like the Netherlands and Bangladesh would largely cease to exist as dry land.

Bearing in mind that we are eventually going to have to abandon fossil fuels anyhow (because they exist in finite quantities), it seems sensible to say that it is worth switching away from them early to prevent the loss of these ice sheets. That is just one of the many climatic consequences that would arise from a particular level of warming. It would be accompanied by droughts, floods, agricultural changes, species relocating, ocean acidification, loss of glaciers, and much else besides. But – to simplify – we can just think about the ice sheets. That lets us set an upper bound for how much warming we can tolerate, which in turn establishes an upper bound for how many fossil fuels we can burn.

Where exactly does that boundary lie? One suggestive fact is that the ice sheets in question formed when the atmospheric concentration of carbon dioxide was about 450 parts per million (ppm). Before the Industrial Revolution, it was at around 280 ppm. Now, it is around 392 ppm and increasing by about 3 ppm per year. Based on a very crude calculation, it may be plausible to say that if we continue on our present course for twenty years or so, we will seriously endanger the integrity of the ice sheets.

The implications of that are pretty huge. Humanity needs to substantially cut greenhouse gas pollution not over the span of 50, or 500, or 1000 years, but over the next couple of decades. Furthermore, for it to be plausible that this change will occur successfully, rich developed countries like Canada need to cut first and fastest. Thus, just by considering one likely consequence of unmitigated climate change, we can make an argument that the complacent attitude of politicians who think we can concentrate on other issues is unrealistic. If we don’t handle this problem now, and we commit those ice sheets to eventual disintegration, people living during the time of inexorable sea level rise will quite rightly view our leaders and our generation as failures, when it comes to taking the most basic precautions to respect the welfare and rights of those who will come after us.

Why care about 2100?

I know it sounds obscure and Klingon to say it, but protecting future generations from climate change is a matter of honour.

As far as scientists can tell, climate change is the most serious major threat facing people a couple of hundred years from now – worse than nuclear proliferation, worse than other environmental problems. If the icesheets really start melting, they will have major problems. How many times in history have dozens of major cities been moved?

At the same time, we have the technology now to stop climate change by abandoning fossil fuels over the span of a few decades. It will be expensive to do that, but it will bring other advantages. Fewer people will die from air pollution. We won’t need to import fuel from dangerous places or produce it in incredibly destructive ways like the oil sands.

It will probably use up a lot of land, but it seems possible that it can be made to work in a way that is fair for all of humanity, with everybody living in comfort.

We are lucky that we live in this generation – the one that will start to pay the cost of decarbonization. That is far preferable to being part of the generation when the actual warming of the planet peaks after all the lags kick in.

The cost of decarbonizing Europe

The European Commission has a plan to achieve the kind of cuts necessary to avoid dangerous climate change:

Europe has set a goal of reducing emissions by 80-95% by 2050. The road map is its first stab at sharing out the cuts… The commission says the investment required to decarbonise power would average about €30 billion ($42 billion) a year over 40 years. This is one of the cheaper parts of the plan; the total cost is about €270 billion a year, with €80 billion going on buildings and appliances and €150 billion on transport. But the commission’s modelling also points to savings on fuel costs, which are low for nuclear and zero for most renewables, of between €175 billion and €320 billion. Other benefits include more energy security and cleaner air.

It’s a massive investment, but it needs to be done, and fossil fuels are expensive too.

Killer coal

Fossil fuels have a negative human impact that goes over and above the climate change they cause:

“One million people a year die prematurely in China from air pollution from energy and industrial sectors,†said Stefan Hirschberg, head of safety analysis at the Paul Scherrer Institute, an engineering research center in Switzerland. More than 10,000 Americans a year die prematurely from the health effects of breathing emissions from coal-burning power plants, according to the Environmental Protection Agency.

Those deaths are another element that can be set against the higher cost per kilowatt-hour of electricity from sources like wind and solar.

A similar estimate on the number of deaths caused by coal in the United States was posted on this site in September 2010.

Oil sands event in Toronto

For those in Toronto who are concerned about the oil sands, one event that may be of interest is happening on April 1st:

No to CETA! CETA and the Tar Sands Teach-in

University of Toronto–OISE Room 2211 at Bedford and Bloor

- What is CETA?

- What does it mean for the Tar Sands?

- Why should we do something about it?

Environmental Justice Toronto is holding a teach-in about the CETA and its impacts on the Tar Sands and communities.

CETA is the Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement–a free trade deal between Canada and the European Union. This trade deal will allow for water, land, and oil to be exploited. Who bears the brunt of this resource exploitation?

Panel discussion, followed by discussion and snacks.

- What does this mean for environmental justice?

- What does this mean for trade justice?

- What do we do about it?

Speakers:

- Clayton Thomas Mueller: Tar Sands Campaigner, Indigenous Environmental Network

- Stuart Trew: Trade Campaigner, Council of Canadians

- TBA: UK Tar Sands Group

http://ejtoronto.wordpress.com/

I don’t know if opposing free trade agreements is a good way to respond to climate change, but at least the event would be a place to learn some things and meet some people who are engaged on the general topic of climate change.

It’s still the time for a carbon price

Over the coming decades, the whole world needs to move from fossil fuel energy to energy sources that do not affect the climate. The intelligent and efficient way to encourage that is to put a price on releasing greenhouse gas pollution into the atmosphere. Right now, people and firms have no financial reason to care how much pollution they are generating. Even a small incentive, in the form of a carbon price, would encourage people throughout the economy to make low-cost reductions in their pollution output.

In addition to establishing a price on carbon, which would initially be low, it makes sense to establish a mechanism through which emissions limits will be tightened and the price per tonne of pollution will rise over time. This will allow people to make sensible investments, and avoid the situation where large amounts of money are invested in facilities that turn out to be deeply inappropriate for the kind of economy we need to create – facilities like coal-fired power plants, coal-to-liquids production facilities, and unconventional oil and gas projects. Ignoring climate change now is like ignoring a worsening toothache – it may save the immediate cost of going to the dentist, but the pain and expense of dealing with the problem later will be much greater.

At a time when governments are struggling to keep their finances in order, the income from a carbon price would be welcome. It could be implemented through a carbon tax, which has the virtue of simplicity, or through a cap-and-trade system with a hard cap on the total allowable amount of pollution per year, and in which the permits that allow a firm to emit greenhouse gas pollution are auctioned.

The ongoing economic weakness in the world economy is not a reason to delay action on climate change. When we ignore the harm produced by our greenhouse gas pollution, we defer an ever-more-serious problem to the future. Not only that, but we are continuing to increase how costly that problem will be to deal with, with every passing month. That is because we are not making the investments we need to make, in the development and deployment of low- and zero-carbon technologies, and because we are encouraging the economy as a whole to continue to invest in the inappropriate, fossil-powered technologies of the past, which are going to need to be scrapped along the road to a safe and renewable global energy system.